The tale of India and its repute is substantial. Home to many ethnicities and almost brimming with rich cultural heritage that dates back to one of the earliest human settlements, this country has borne countless stories that have been etched onto its soul. Every community and its explorations through the ages from different parts of the country has contributed to this epic. This is an endless tale and its writing remains in progress to this day.

Through innumerable eras of various cultural influences and transformations of style, India had written its rich fundamental forewords. However, when the country finally stood on its own feet to build a national identity to be on par with the world, there was a dilemma.

As a newly emerged homogeneous nation, its ambitions to modernise the face of the country or to revive its idealised past posed a challenge for the State and the visionary architects of the time to explore.

In Search of an Identity | Nation building

With the onset of Independence, the building of the nation, or rather the creation of a shared identity as a community at the national level had become the utmost priority. Policymakers and the leaders of the State sought to achieve stability of the nation by ensuring welfare and efficiency of the habitat the citizens were living in, all the while focusing on the country’s economic growth.

The built environment is believed to be a direct reflection of the inhabitants’ character and that it captures the essence of their lives and practices. So naturally, following the development of a social harmony came the right decision to seek architecture as a medium to present India’s glory to the world beyond.

Such was the intention of the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, for he had invited one of the pioneers of modern architecture, Le Corbusier, for his expertise in designing the city of Chandigarh and its civic infrastructure. These buildings seemed raw on the skin and expressed Brutalism, but they signified great power and authority as they were meant to.

American architect Louis Kahn’s awe-inspiring architecture for the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, consisted of bold forms and exaggerated volumes and voids, following a similar approach but built of brick. Hence, the 1950s saw an introduction to a new language of architecture in India, one that explored new geometric forms and their iterations in exposed concrete and brick.

Soon, Indian-based architects who had attained education abroad had returned and had taken charge of writing the new chapters in the country’s continuing saga and gaining international recognition for the same.

Architects like B.V. Doshi, Charles Correa, Raj Rewal, etc., had followed along the trail that had been set preceding their take over. Their style consisted of the new language established during the period such as exposure of the well-composed geometrical buildings with the truest form of the materials used, but also, they contained within themselves an aura of regionalism.

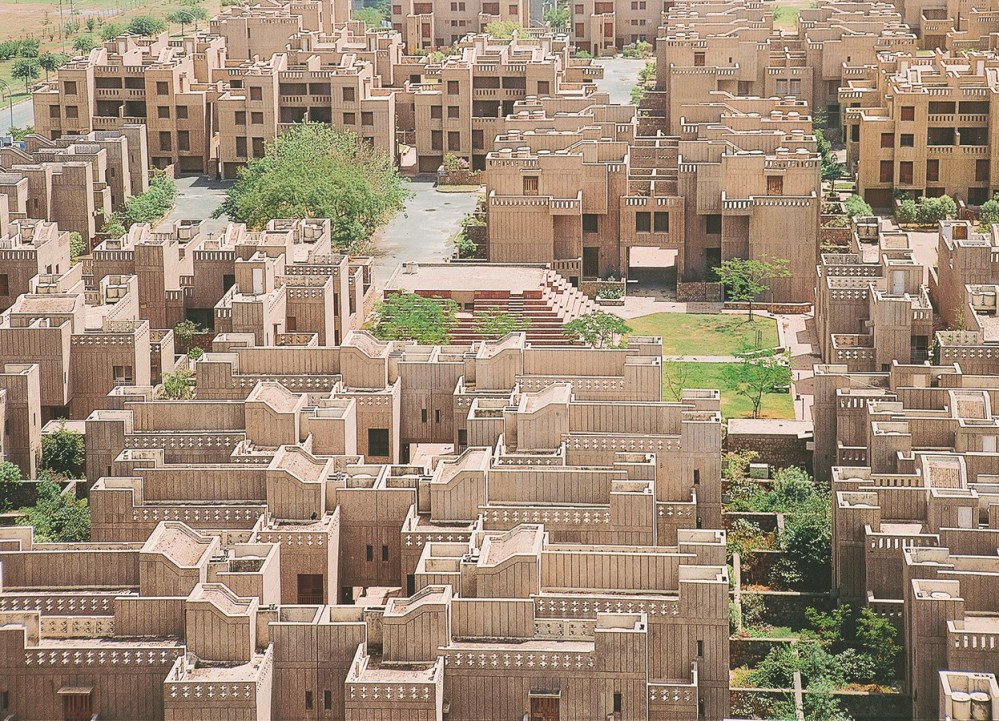

The Asian games village complex by Raj Rewal in New Delhi transports people to the traditional village of Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, with its characteristic entrance gateways, linked terraces, courtyards and gardens. It replicates the experience of walking through the narrow lanes and the sense of community that a village offers.

At the Hall of Nations at Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Raj Rewal exhibited a great advancement in technology among infrastructure projects of the time with the use of large span space frame structures that acted as sun-breakers or rather a reinterpretation of the traditional ‘jali’. The architect himself stated this project as a “symbol of achievement by young architects in a Newly-Independent India, creating a style which could be constructed with limited means, yet be uniquely Indian”.

Recent Pritzker Awardee, B.V. Doshi is responsible for architecture education to aspiring students in Ahmedabad where he set up the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology. He had perceived the process of learning quite differently, as opposed to the conventional classroom concept and aimed to “create an atmosphere where you don’t see the divides and doors”.

These ideologies were reflected in the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore where he had articulated a network of courtyards and green corridors between the learning spaces to encourage academic interactions to be carried beyond classrooms. The spaces were crafted to allow an interplay of light and shadows, solids and voids as inspired by the town Fatehpur Sikri during the Mughal reign.

Perhaps the architect most sensitive to the traditional context and regional vocabulary was Charles Correa. Practising a concept that was termed as “Critical Regionalism”, he often combined principles of Vastu Shastra modified to modern functionality and utility as an approach in designing his projects.

His project, the Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya in Ahmedabad is a contemporary modular pavilion that showcases modesty and simplicity while enhancing the spirit of ‘Swadeshi’.

This new chapter of the developing face of architecture in India had been drafted, each in their form of representation, by various architects. But they had all, undeniably, strived to build a common notion of ‘Indianness’. What came next was the responsibility to publish and gain global recognition for the transitioned persona of the country and an opportunity to narrate its tale.

In Search of Recognition

Showcasing the architectural scene in the country was, in a way, a mode of presenting its riches and strengths as well. The country was not always one among the world superpowers like it is known to be today and it took decades of external public relations through participation in International exhibitions and publications in professional journals to enable the world to grasp the skills and capabilities produced by its citizens.

In the 1980s, the Government of India had commissioned exhibits for the Festivals of India that were organised in France, USSR and other countries. The first of the exhibitions was curated by architects Raj Rewal and Ram Sharma in France in 1985 and it was three-fold.

The first two sections showcased the framework of Indian architecture as the ‘wonder that was’ and subsequently the Indian brand of modernism. The third section of the exhibition focused on the works of Le Corbusier and his contribution to the developing country.

In the following year, a team led by architect Charles Correa had curated the exhibition in the USSR. Titled Vistara, meaning limitless expanse, this exhibition has also managed to give insights into the various chapters of growth under categories, namely, Roots/ Present/ Future.

The pen has not been rested yet and the ink still flows persistently, as smooth as ever. Discoveries and the generation of innovative techniques to improve the quality of life with the best of facilities remain the immortal goal of the country. The study and practise of architecture—its true intentions and importance, has been placed under the spotlight in recent decades and it has now become a growing pursuit.

While framing the understanding of spaces and striving to achieve healthier environments, buildings and their inhabitants have been co-existing by depending on one another. This has led to these preconceived inanimate structures becoming a part of the living. India’s infrastructure has been proudly printed as its cover page as it reveals a single impactful image, one that has been compiled from multiple entities.

This ever-lasting account will continue to have climaxes, turning points and variance in language, but keeping its earliest of pages still intact it is bound to receive exceptional reviews and earn a spot on the highest of shelves.

References:

- Menon, A., 2021. The Contemporary Architecture of Delhi: a Critical History. [online] Architexturez.net. Available at: <https://architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-21213> [Accessed 27 March 2021].

- Curve.carleton.ca. 2021. [online] Available at: <https://curve.carleton.ca/system/files/etd/b3ca472c-d6f2-4852-b30f-0c923edd118e/etd_pdf/7e2a884fa17e918d9b1cbd67ed78158b/sproul-architecturesroleinnationbuildingthepalest_col.pdf> [Accessed 27 March 2021].

- Jetir.org. 2021. [online] Available at: <http://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIRC006253.pdf> [Accessed 27 March 2021].

- ArchEyes. 2021. Gandhi Memorial Museum & House (Sabarmati Ashram) / Charles Correa. [online] Available at: <https://archeyes.com/sabarmati-ashram-museum-gandhi-residence-charles-correa/> [Accessed 27 March 2021].

- Iimb.ac.in. 2021. You are being redirected…. [online] Available at: <https://www.iimb.ac.in/about-institute/architecture> [Accessed 27 March 2021].